Alison Miranda, our director of learning and assessment, unpacks the ecosystem approach guiding FGHR’s new theory of change.

We navigate complexity every day in our lives, whether managing our schedule to arrive home on time for dinner or coordinating with neighbors to hold a community clean-up event.

These may seem like simple events that we can control or maybe even do on our own. But the reality is there are so many factors—from a late bus or a sudden rainstorm to other people with their own infinite complexities—that influence how these events unfold and what results emerge. In reality, we do very little on our own.

Reflecting on the unknowns of our daily lives helps to contextualize the immense complexity entailed in struggles for human rights. Each regional context where activists are pushing for justice entails countless factors beyond any individual’s control. Neither we nor any one activist can realize change alone.

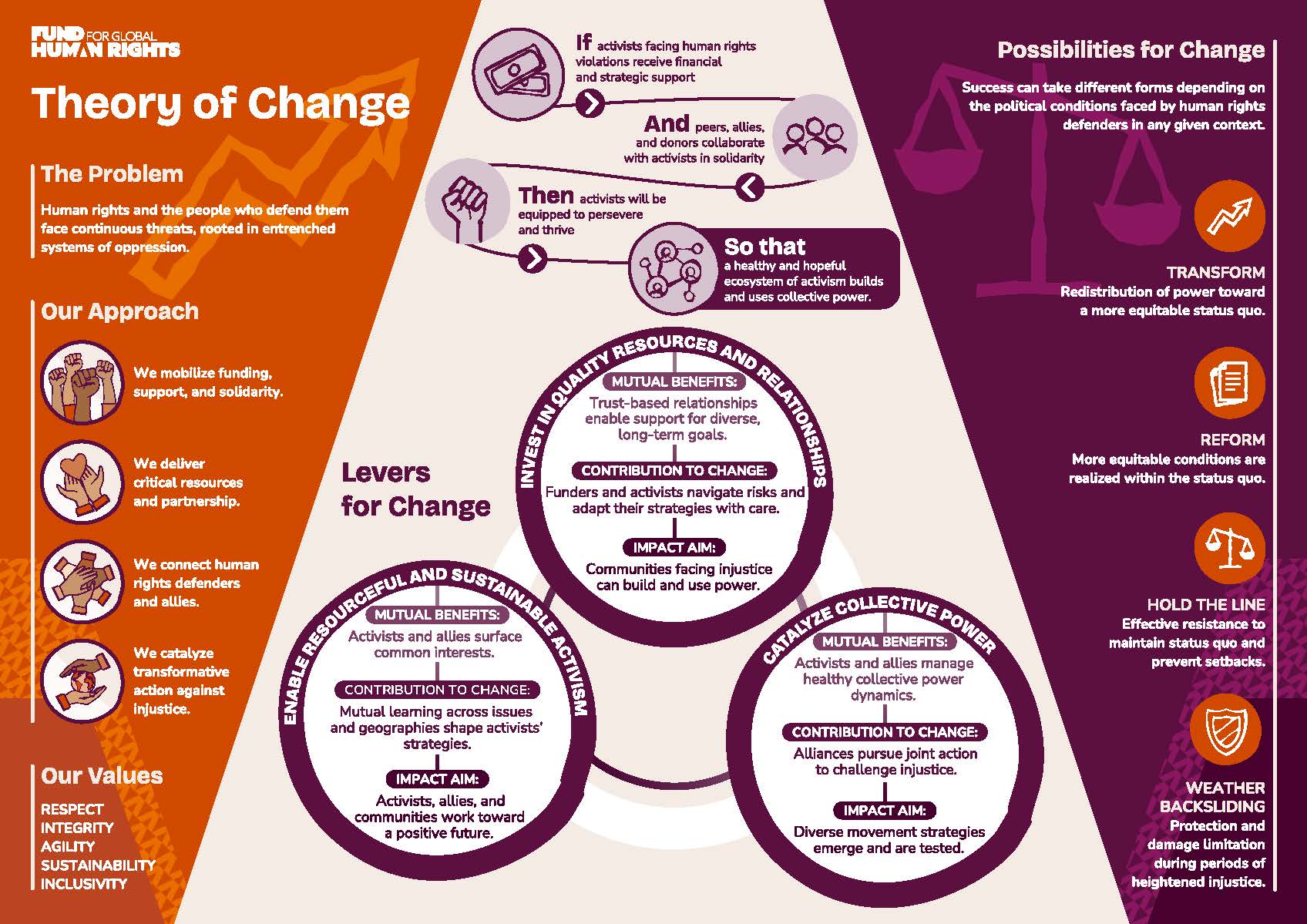

That’s why our refreshed theory of change, building on our five-year strategic outlook, prioritizes an ecosystem approach.

Rather than suggesting a single, linear pathway to change, an ecosystem approach recognizes the complexity of the world around us and the importance of collaborating with others. It is an approach that goes deeper than symptoms to the root causes of challenging problems and to manage shifting conditions.

Unpacking Our New Theory of Change

Our updated theory of change is designed to sharpen our focus and analysis at this critical moment for human rights around the world.

Over time, as civic space has closed in many regions where we work, our strategy has evolved to explicitly prioritize building the collective power of movements. Ultimately, we are always striving for better laws and policies, but we know that traditional policy advocacy isn’t always the best way to get there. Building durable systemic change requires deep collaboration between diverse sets of people.

This strategy requires us to think beyond typical approaches to funding: we need to show up with creativity, resolve, and solidarity as an active partner to grassroots groups around the world. These principles are central to our revised theory of change, which sets out the different strategic levers that can enable movements to build toward shared visions of rights and justice as a roadmap for our resourcing and allyship.

Our work is motivated by the desire for deep and far-reaching improvements in human rights and justice issues: we draw inspiration from countless examples, including the advances achieved by the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa, the women’s reproductive health rights movement in Latin America, and successful struggles for LGBTQ+ equality across the globe. But context always matters and this type of transformative change is not always the most viable or relevant immediate goal—because progress and success can take very different forms depending on the political, social, or economic conditions that human rights defenders face in any given context.

Drawing on existing literature, our theory of change names four different possibilities for change to recognize the variety of contexts in which FGHR grantee partners work and to value different types of outcomes.

Far too often, funders may be drawn to only support work that appears to offer immediate opportunities for progressive change. But it is also vital to stand with movements facing deeply repressive conditions. Even in instances where the potential for short-term impacts seems limited, contexts can rapidly shift. From Syria to the Philippines, activists have demonstrated time and time again how, backed by flexible funding and international solidarity, they are able to hold the line and build toward long-term change.

Our theory of change provides a compass for our grantmaking as we navigate the rapidly shifting possibilities for change in each of the regions where we work.

Evolving and Adapting in Turbulent Times

At a time when activists face growing authoritarianism and are fighting to ensure that the international human rights framework itself remains relevant, a theory of change is more than a thought exercise. It is a tool to help us to imagine hopeful futures, fuel creative adaptation, and act on our insights toward a more just and equitable world.

I have personally worked to develop theories of change and to measure and manage outcomes many times throughout my career. But this is the first time I have thought about how change happens during such a turbulent period of shifts globally. As I worked with colleagues and consulted peers and other experts to develop this theory of change, my own perspective shifted.

Rather than a framework used to aggregate results, I have come to think of a theory of change as an umbrella to hold the diverse work and contexts of my colleagues and the grantee partners we support. It is a common language to explore our successes and setbacks and to connect our insights.

Too often, things like evaluation reports, learning agendas, or theories of change are workshopped to death, revised endlessly, and shared only when perfect—only to gather dust on the shelf. But our goal isn’t a perfect document, it is continuous learning and adaption. What we are sharing now is just the foundation: the real work will be to apply this framework on an ongoing basis, analyze the evidence, and continue to adapt our approach as conditions evolve.

This isn’t the last word. It’s a work in progress—just like change itself.

Alison Miranda is director of learning and assessment at the Fund for Global Human Rights.